Are any of you familiar with the book, How to Be an Adult, by David Richo? It was first published back in 1991. It’s a little book, but succinctly packed with wisdom on psychological and spiritual integration. While it feels a little strange to pick up at 48, I don’t know that it would have the same impact if I read it as a young adult. I just wasn’t ready for it then. And I really wasn’t ready for it in my 30’s. As Anne Lamott says, “At 33, I knew everything. At 69, I know something much more important.” Boy, did I know everything in my 30’s! There was no way I was going to acknowledge the bag I was carrying on my back that revealed some of these shadowy parts discussed in How to Be an Adult. I’m just old enough now to understand I have a way to go in learning the important stuff, and to even be excited about it.

Anyway, back to this book. It’s a lot of personal work. Richo spends Part One on challenges to adulthood such as growing up, assertiveness, fear, anger, guilt, and values and self-esteem—doozies, right? It’s hard to choose one to write about. As I read the anger chapter, I was thinking about the extra challenge this is for women—maybe especially women in the church—because women aren’t supposed to ever be angry. But I think it is a challenge for men as well, who often are shown the way they are to express their anger is through rage. I’ve been a recipient of a lot of rage on the internet from officers in the church.

Richo gives this definition for anger:

“Anger is the feeling that says No to opposition, injury, or injustice. It’s a signal that something I value is in jeopardy.”

It may or may not be rational, but the “psychological energy of anger comes from a real or perceived threat.” And we can still express our anger legitimately as a feeling we are experiencing, even if it doesn’t have objective justification.

We can express our anger actively or passively. We can stuff it down and deny it. We can mask it with guilt. But anger always makes it way out in some form. The truth is that we all get angry at ourselves and one another in relationship. But Richo believes that many of us have never seen real anger (a true feeling), only drama (an avoidance of true feeling). Let’s talk about how that shows.

Directly: by the expression on our faces, raising our voices, and gesturing

Passively: when we punish the offender without admitting our anger. Some examples are “tardiness, gossip, silence, refusal to cooperate, absence, rejection, malice to cause pain.”

“Strongly expressed anger is called rage. Strongly held anger is called hate. Unexpressed anger is resentment. Anger can be unconsciously repressed and internalized. It then becomes depression, i.e., anger turned inward.”

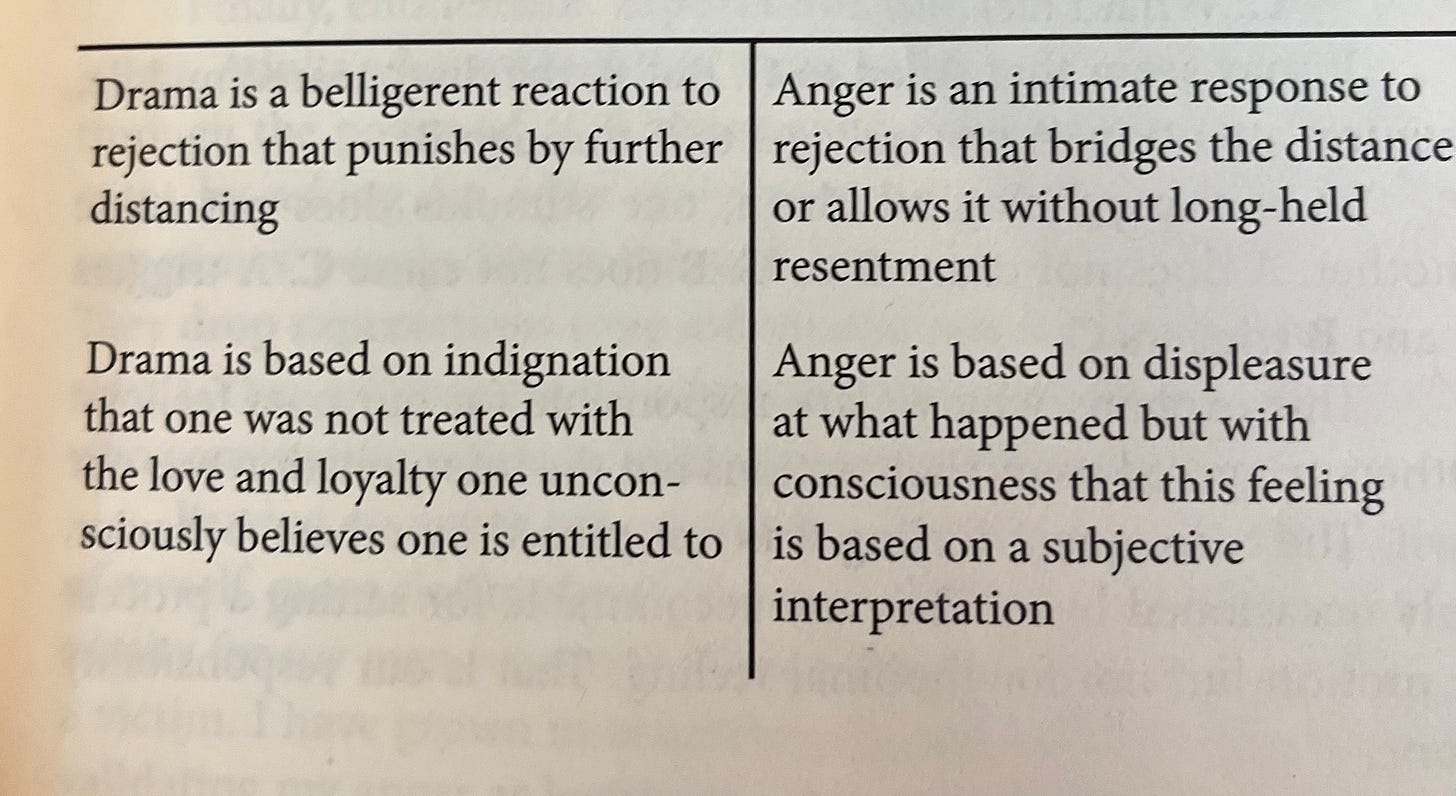

It takes courage and maturity to drop the drama and deal responsibly with our anger. Richo explains that the “neurotic ego clings to negative excitement.” But as we exercise our functional ego as mature adults, we begin to learn and maybe even love the positive excitement in expressing our true feeling and then being released from it. He says that anger is the shortest feeling, not something we can “hold onto” once expressed properly. What we hold onto in our drama are the stories we are telling ourselves to keep the drama ignited. Here is a helpful chart from the book distinguishing drama from true anger:

Whatever the trigger, we are responsible for our own feelings. Richo uses a model based on the work of Albert Ellis to face our anger responsibly:

An Action occurs (open to any interpretation)

My Belief interprets the action in a certain way

A Consequence occurs: the feeling based on the belief that was triggered by the action

Other psychologists described this process as being kind and curious with ourselves about our feelings. What am I feeling right now? What information are my feelings giving me? What value of mine is being threatened? Has something happened to me before where these values or beliefs were threatened? Is this reopening a wound? What story am I telling myself about this person? Our anger is pointing to where something still hurts, and we need to address that. When we do, we can then have responsible confrontation and ask for amends, rather than acting aggressively and dramatically. Of course the maturity of the other person will inform how we move forward. But we are responsible for ourselves.

Easier said than done, I know. But we can begin to view our anger as valuable “lively energy” directing us to our growth, finding a positive power there that doesn’t need masked, stuffed down, or denied. Our anger can then be transformational.

What does all this have to do with finding the poem in the church, the tagline of my Substack? Besides the immaturity of so many leaders and the way they harm with their dramatically expressed anger because they won’t do their own work, besides the fact that we don’t feel safe in church to express our anger, and besides the cockamamy teachings in the church that feelings don’t matter, we shouldn’t listen to them, and the faulty ways we measure sanctification, I saw some shaming recently online over whether or not we can get angry with God. That disturbed me.

Do we think God doesn’t know when we are angry with him? Don’t we see God drawing that anger out of his own people throughout Scripture? What do we do with our anger if we do not face it? How do we mask it? Who do we harm with it? Aren’t we acting against Jesus when we harm others with our projected anger? What if we could bring our anger to God in this curious fashion and let him help us to get to the fears and wounded values that provoked it. What if God is big enough to hold our anger with us and help us to face hard things? Maybe these pastors online were shaming others for talking about sharing their anger with God because they only know anger as rage. Maybe they have never seen real anger, only drama. Maybe God is calling us to grow up.

Once again, Fred Rogers was teaching us well, if we only listened.

https://www.misterrogers.org/videos/what-to-you-do-with-the-mad-that-you-feel/

As Anna pointed out on my Substack, this resonates with what I just posted re Psalm 88. It is tempting to read Psalm 88 as dramatic, angry accusations against God. But it gives voice to true anger. At least I’m wondering about Richo’s descriptions of true anger as a lens for Psalm 88. Seems to fit pretty well.